By Yanik Nyberg, Seawater Solutions Founder & Director

2021 is well under way for us at Seawater Solutions, with seven of us now all over the world,

from Ghana to Malawi and Vietnam. The end of 2020 felt like a rush to the finish line to get our current projects launched in light of Covid-19 and the logistical nightmare that this presented, but we still managed to catch a short breath and reflect on the year that 2020 was, and what a year it turned out to be!

2020 started out with high hopes for expansion and impact. It’s crazy to think that at the time there were only four of us, three full-time staff. One year on our team grew to a whopping 11!

In January 2020 I started my trip in India, at the Bay of Bengal, working with a local NGO to explore the problems and opportunities facing coastal communities in the states of West Bengal and Odisha. There we discovered that a potent mix of climate change, rising sea-levels, salinisation, and overfishing had taken its toll on communities and their livelihoods. A familiar narrative unfolded that we’ve seen all over the world. Irregular rainfall brought on by climate change impacted local agriculture and resulted in salt build-up in farmland, pushing farmers into a ‘race to the bottom’ fishing sector that was already close to depleting marine resources, and seawater intrusion due to rising seas salinized groundwater and wells creating localised water crises and even leading to a huge increase in miscarriages as women in these communities drank increasingly salty groundwater.

Meeting with community leaders and NGOs in Odisha’s salt affected communities – January 2020

Soon following, Nick joined me in Bangladesh from Vietnam to launch our integrated seawater farming projects in the Khulna region and in Cox’s Bazaar, where one million Rohingya refugees were relocated following the genocide that started nearly four years ago. Bangladesh is a rapidly developing country, yet faces a disproportionate amount of climate-induced threats like flooding, salinisation, and the displacement of over a million people every year.

Our objectives in Bangladesh involved the utilisation of degraded and flood-prone land to grow halophytes (salt-loving plants) for food and ecoservices like flood adaptation and carbon sequestration. In total, we started six pilot farms on a variety of land, including salinized rice fields, degraded salt pans, and shrimp farms.

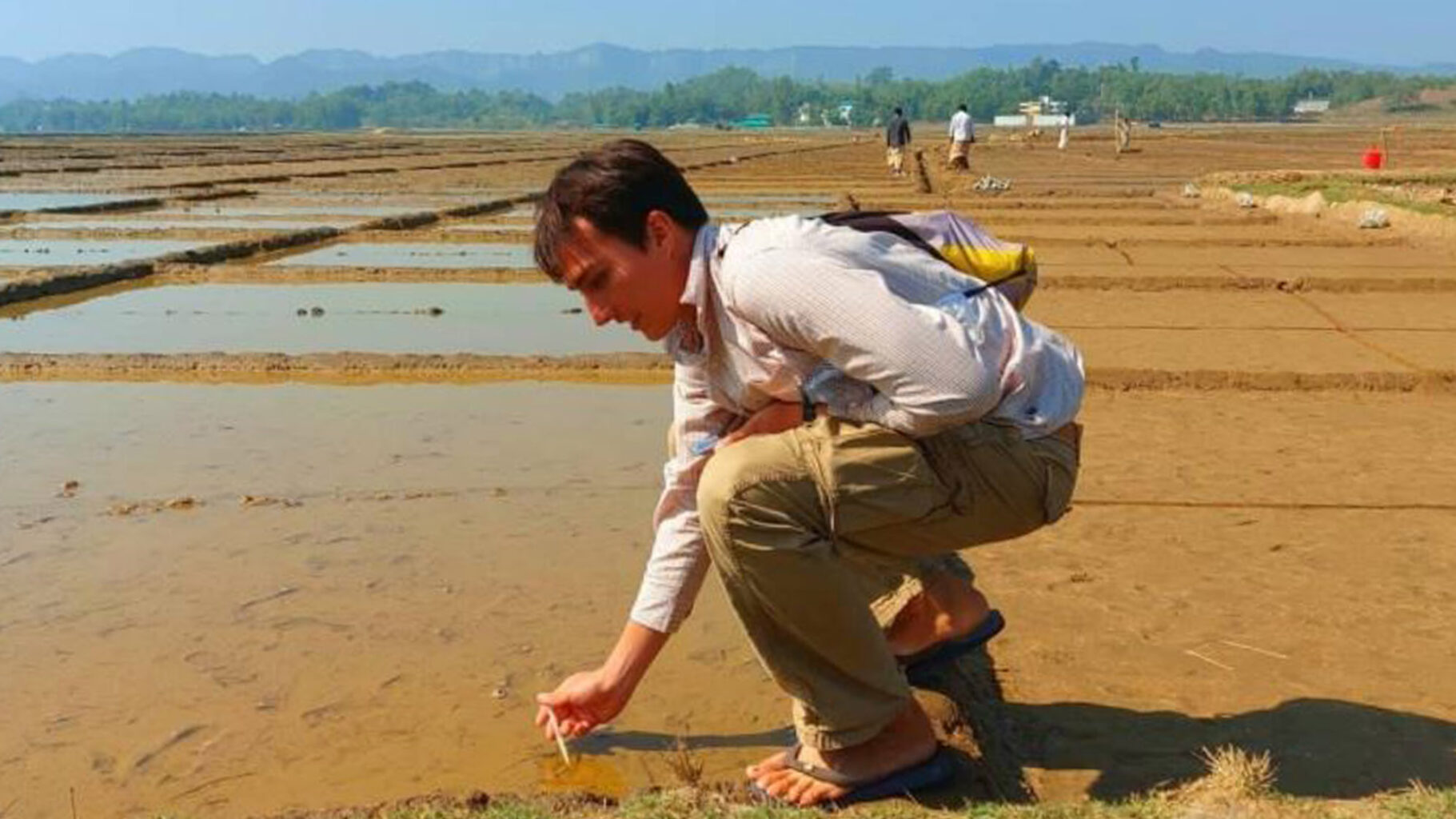

Preparing salt-affected rice fields for seawater farming in Bangladesh – February 2020

Nick taking water and soil samples on one of the sites near the refugee camps in Bangladesh

A healthy constructed wetland where degraded rice paddy fields stood two months prior – Bangladesh

The shrimp aquaculture farms highlighted another harrowing ‘race to the bottom’ narrative.

Many of these aquaculture farm ‘pits’ started out as mangroves centuries ago. They were soon cleared for rice farming, but as seas rose and storms became more severe, seawater became a much greater threat. Instead of four harvest a year as we see in some other Asian countries, farmers in Southern Bangladesh often only harvest once in the rainy season. The rest of the year the land lies idle, too salty to farm. Compounding this issue is the loss of nutrients and soil health caused by salt and rising seas, which leads many farmers to create ponds in which they can farm shrimp or finfish instead. But with the sheer amount of waste produced by these fish, and no proper wastewater treatment, disease begins to spread and the water becomes inhospitable to the fish, resulting in the abandonment of these aquaculture ponds as far as the eye can see. As a result, more mangrove forests are cleared to make room for more aquaculture ponds. A vicious cycle.

Working with aquaculture has always been a key component of our work. The waste produced from fish farming is a valuable resource in crop production, using this as organic fertiliser to grow food and limiting the need to introduce chemical fertilisers. Fortunately, halophytes, specifically our Salicornia (Samphire) plants are among the best hyto-remediators in the world, taking in an astonishing 99% of waste, while neutralising it in the process. Even more incredible is the ability to use these halophytes to feed fish and shrimp, substituting up to 60% of conventional fish feed that mostly comprises fishmeal made from the destructive harvesting of wild marine catch and soy linked to the deforestation in the Amazon. This is where the term ‘integrated seawater farming’ originates.

The results of these pilots were staggering. Within three months of sowing, our plants were thriving in all land categories, and we were able to have a first harvest within two months. On the aquaculture sites, our Salicornias were able to remediate soils rapidly, allowing for shrimp farmers to increase their operations while the shrimp had a ready supply of food growing right under them. Unfortunately a few months into the year in April, the largest cyclone in a hundred years hit the Bay of Bengal and decimated much of the coast in Bangladesh and India. Covid-19 soon followed and we were forced to put our projects on hold for the time being. One year later, we’re thrilled to announce that we will be returning again in a month’s time to launch a much larger project with our partners ICCO and the World Food Programme, involving 600 smallholder farmers.

I returned to Scotland at the end of February, just ahead of the first lockdown, and Nick returned to Vietnam to launch the next set of integrated farms in partnership with landowners and aquaculture companies. In Scotland, It became clear that agriculture wasn’t Covid-proof.

While there was a huge amount of uncertainty in the farming community around markets, logistics, and safety, one of the main threats impacting innovation in farming was the willingness of farmers to take on risk, or to engage in new approaches in such a trying time.

This unfortunately led to the postponement of one of our earliest sites in Ayrshire, but also resulted in the exploration of other partnerships and projects to explore. This led us to the Highlands of Scotland, where we launched a project using underutilised grazing land to build wetlands and grow food with saltwater. In the highlands alone, there are hundreds of thousands of hectares of land such as this that is used by little more than a few sheep, representing a huge opportunity for nature-based solutions and food production.

Turning wasteland into carbon capturing saltmarshes in the highlands, powered by sun and wind

Highland Samphire, a first in the UK, grown with seawater in Glen Shiel

With a few delays and a bumpy start, our Glen Shiel project, funded by the Highlands and Islands Make Innovation Happen Fund, resulted in a fantastic proof of concept that such marginalised land could bear fruit to high market-value crops, and showed that the Highlands could once again be home to a rich and diversified agriculture community as it once was before the Clearances, where over 60 types of crops were grown. We were incredibly grateful for the opportunity given to us by the Burton Trust to develop these pilots, and to offer the estate house for us to stay in during our time there.

One of the most exciting new products we’re developing with our partners at SaltyCo are textiles made with no freshwater. We’ve been trialling salt-tolerant reeds in Scotland and elsewhere to tackle the environmental threats caused by conventional textile production, namely water scarcity and chemical pollution. Check out SaltyCo’s website for more on their impactful innovation! https://saltyco.uk/

During the summer months of 2020 we were thrilled to welcome new members to our growing team, including Mario Ray, Chris Eccles, and Samuel MacKinnon, who together brought a wealth of expertise to the company, from international development coordination to environmental monitoring, and public policy.

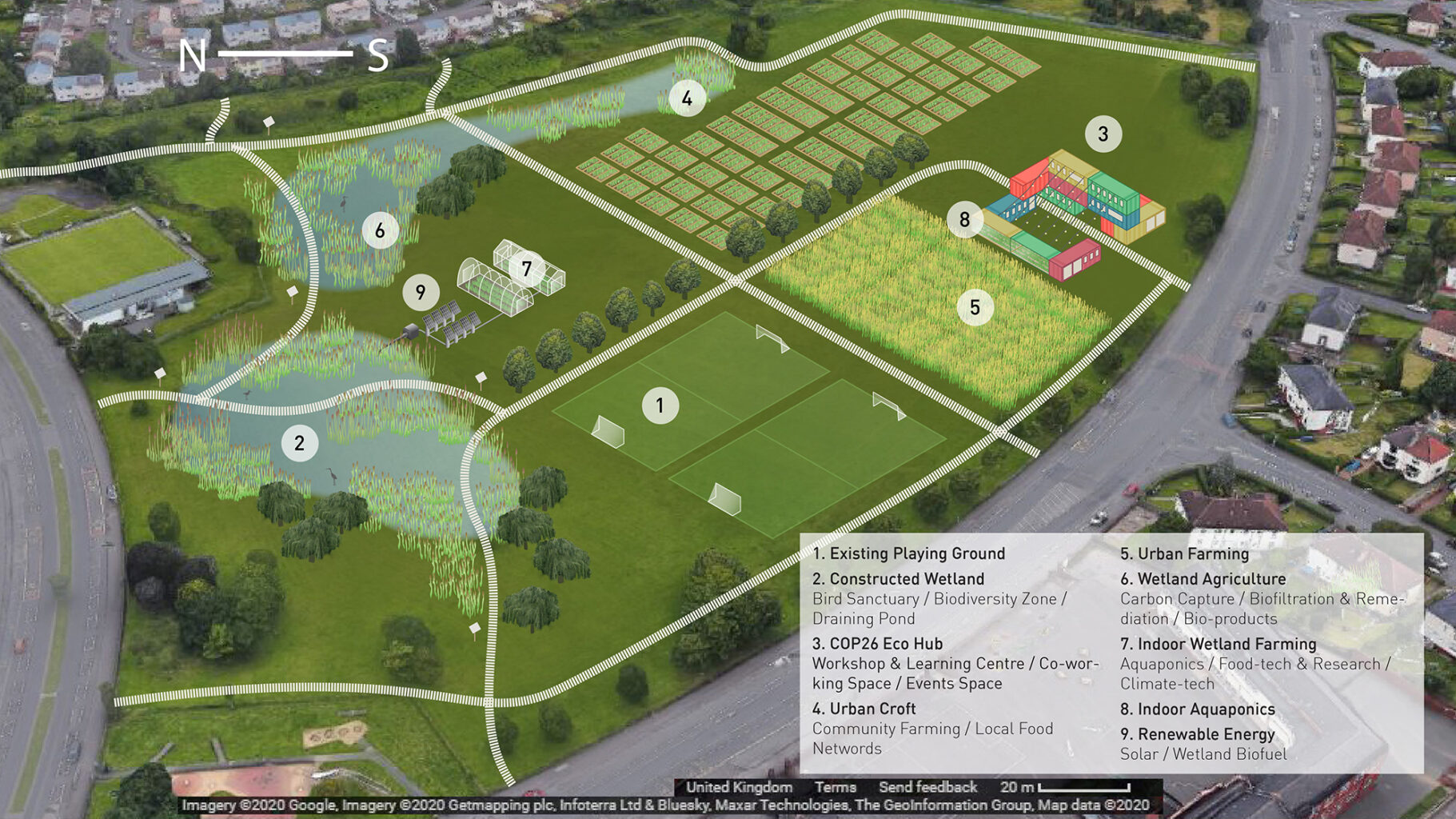

This growth led to the development of one of our most ambitious projects, the Glasgow Wetland Carbon Capture Project (GWCCP). In June we were awarded £60,000 from the Central Government’s Sustainable Innovation Fund (Innovate UK), to develop Europe’s first wetland climate park ahead of COP26 that will take place in Glasgow in November of 2021. This exciting project, in partnership with the University of Strathclyde, UKUAT, and Glasgow City Council, aims to turn underutilised parks and brownfield land into thriving wetland ecosystems where carbon can be captured and wildlife is supported. The project will also feature eco-hubs where indoor wetland and vertical farming can take place to grow food locally and educate communities around climate-smart food production. Phase 2 of the project will commence in March of 2021 with up to £2.5 million in funding. We’ll hear next month if our bid is successful, and will spend much of 2021 developing these sites around Glasgow with local food growers and academic institutions.

The GWCCP will build networks of Climate Parks in Glasgow to support local food production and socio-environmental objectives

Chris Eccles, Seawater Solutions’ environmental coordinator taking samples from wetlands for the GWCCP

The GWCCP Phase 1 project took us up to this past Christmas, on which Samuel and I flew to Ghana on Christmas eve to launch our Saline Aquaculture Network Ghana (SANGHA) project.

Soon afterwards, Chris and Mario flew to Malawi to launch a similar project, Saline Agriculture for Climate Adaptation Malawi (SACA Malawi). These two projects, with over £500,000 in funding by DFID and Innovate UK, address the problems of salinisation, rising sea levels, and the degradation of wetlands by introducing saltmarsh farming and sustainable aquaculture to target regions suffering from these threats.

Our Ghana team will be staying over there until March, while Chris and Mario will be returning to the UK in February. On our way home, the African crew will be making a stop-over in Namibia, where we are partnering with a desalination plant to use brine (desalination concentrated seawater) to turn the desert into a green food-production hub. More to come…

That should about cover it up to now. Looking back on 2020 I think it’s fair to say that we’ve exceeded our wildest expectations, though not always as planned! I think I speak for the team when I say that we cannot wait to see what 2021 has in store for us.

Finally, we want to extend a huge thank you to so many of you that have supported us in so many ways this last year, and have believed in our work here at Seawater Solutions. Thank you!

We’ll be sure to keep you updated, from our monthly newsletters to hopefully seeing each other in person soon. We wish you a great start to the year and hope to hear from you soon, our door is always open!